|

|

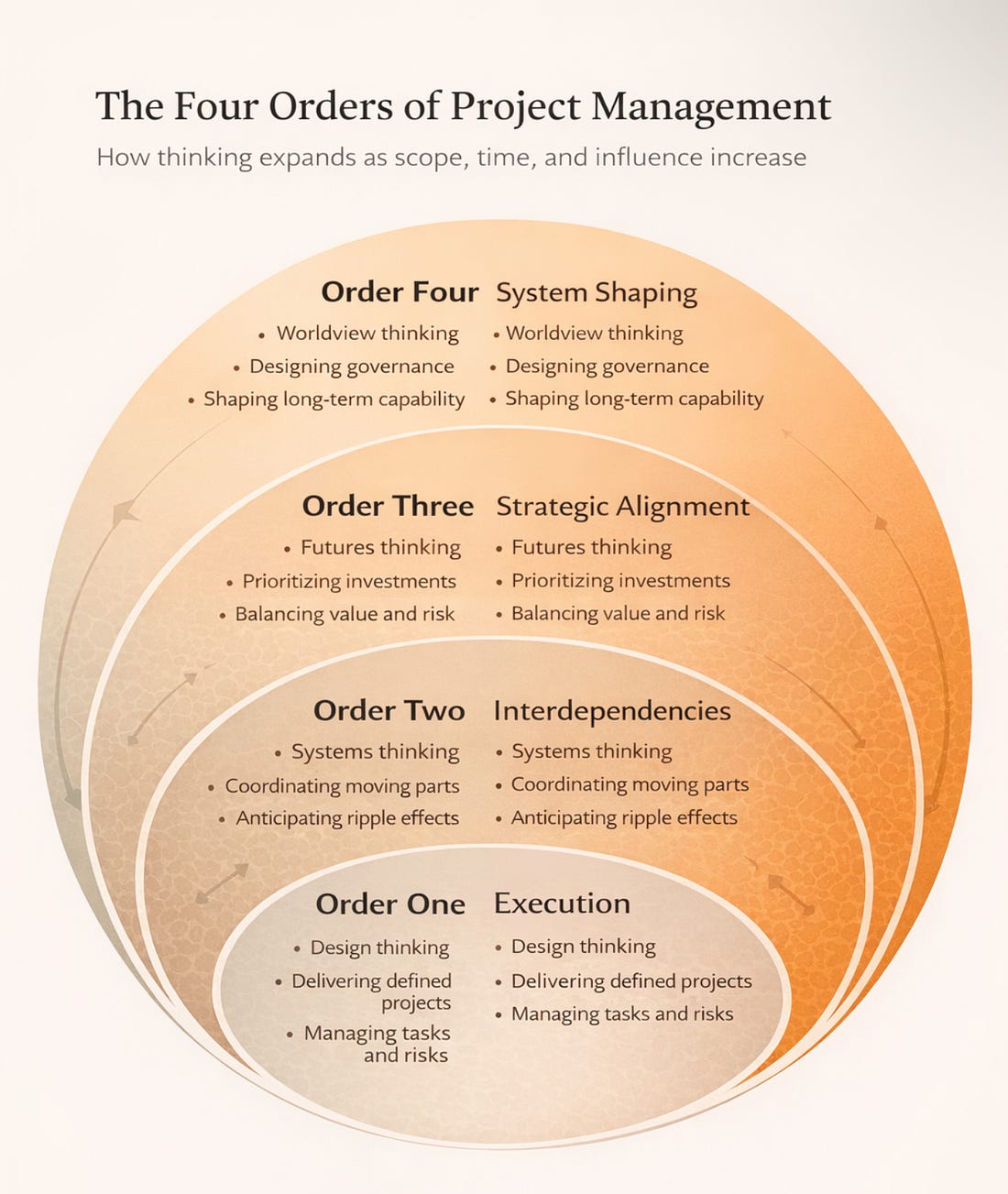

Project management does not become more advanced because projects get larger. It becomes more advanced because the way a project manager understands change evolves.

Early in a career, the work is concrete. There is a scope to deliver and a plan to follow. Over time, the work expands outward. Projects start interacting with other projects. Decisions begin to affect strategy. Eventually, the work moves upstream, shaping how projects are conceived, governed, and sustained.

These shifts are not about hierarchy or job titles. They are about orders of thinking. Each order represents a different way of seeing the work and a different relationship to time, complexity, and impact.

You do not leave earlier orders behind. You carry them with you.

First-Order Project Management: Designing and Delivering the Work

First-order project management is grounded in execution. The goal is clear. The outcome is defined. The work is to translate intent into reality.

This is where most people enter the profession, and where disciplined craft is developed.

What the work looks like

At this level, the project is treated as a bounded effort. It has defined inputs, outputs, and constraints. The project manager is close to the work and deeply involved in how it unfolds.

The focus is on:

Clarifying scope and deliverables

Breaking work into manageable components

Sequencing tasks correctly

Tracking progress and risks

Keeping commitments

Tools and frameworks used

This is the domain of foundational tools:

Work Breakdown Structures

Gantt charts and schedules

RACI matrices

RAID logs

Status reports

Used well, these tools are not bureaucratic. They are design instruments that shape how work moves.

How thinking works at this level

First-order thinking is intentional and linear. You assume that if the work is framed clearly and executed carefully, results will follow.

There is also an implicit design mindset at play. You are taking an abstract need and making it tangible. Plans, schedules, and reports are not neutral documents. They are artifacts that influence behavior.

A strong first-order project manager designs these artifacts thoughtfully. They make the work legible to others.

An analogy

This level is like skilled craftsmanship.

You are building something with your hands and your attention. Precision matters. Preparation matters. If the foundation is weak, nothing above it holds.

Why this level matters

First-order mastery builds trust. It establishes credibility. It proves you can deliver.

Every higher order depends on this competence. Without it, strategy remains theoretical.

Second-Order Project Management: Working With Systems and Interactions

Second-order project management begins when the project stops behaving like a closed system.

Dependencies appear. Stakeholders pull in different directions. Changes ripple across teams. The project manager’s role expands from executing tasks to managing interactions.

What the work looks like

At this level, the project manager starts paying attention to relationships.

The focus shifts to:

Interdependencies between teams, systems, and decisions

How changes propagate across the project

Stakeholder expectations and influence

Feedback loops that amplify or dampen issues

The work becomes less about pushing tasks and more about maintaining balance.

Tools and frameworks used

Second-order work relies on visibility and awareness:

Dependency maps

Integrated schedules

Change impact analyses

Stakeholder maps

Risk heat maps

These tools help you see how the system behaves rather than just what it produces.

How thinking works at this level

Second-order thinking is systemic.

You stop assuming that problems live where they appear. You start asking what conditions produced them. You recognize that small changes can have outsized effects.

Instead of asking, “Is this task late?” you ask, “What does this delay affect, and why?”

An analogy

This level is like managing traffic rather than driving a single car.

You are watching flow, congestion, timing, and coordination. Success is measured by how smoothly the whole system moves, not just one lane.

Why this level matters

Second-order project managers prevent complexity from turning into chaos. They absorb volatility so teams can stay focused.

They are translators, stabilizers, and sense-makers.

Third-Order Project Management: Choosing the Right Work Over Time

Third-order project management marks a fundamental shift. The unit of concern is no longer the project. It is the portfolio.

Here, the central question becomes whether the work should exist in its current form and how it fits into a broader direction.

What the work looks like

At this level, projects are treated as investments.

The focus includes:

Strategic alignment

Portfolio balance and sequencing

Capacity and funding constraints

Long-term value and benefits

Not every project can move forward. Not every initiative deserves equal attention.

Tools and frameworks used

Decision-making tools become central:

Portfolio scoring models

Strategic roadmaps

Benefits realization frameworks

Capacity planning models

OKRs and KPIs tied to strategy

These tools support choice, not control.

How thinking works at this level

Third-order thinking is forward-looking and plural.

You stop planning for a single future and start preparing for multiple plausible ones. You evaluate decisions based on how they perform under uncertainty.

You think in horizons rather than deadlines.

An analogy

This level is like managing an investment portfolio.

Individual projects matter, but only in relation to the whole. You care about timing, diversification, risk exposure, and long-term return.

Why this level matters

Third-order project management protects the organization from overcommitment and drift. It ensures effort is directed toward outcomes that matter over time.

This is where judgment, restraint, and executive communication become critical.

Fourth-Order Project Management: Shaping the Conditions for Change

Fourth-order project management operates upstream of projects and portfolios.

Here, the work is not to deliver initiatives, but to shape the system that produces them.

What the work looks like

At this level, the focus shifts to:

Governance structures

Decision rights and incentives

Organizational learning

Long-term capability and resilience

You are no longer managing work. You are designing how work enters the system and how decisions are made.

Tools and frameworks used

Fourth-order tools are architectural:

Governance models

Operating model design

Policy and standards frameworks

Knowledge management systems

Feedback and learning loops

These tools shape behavior indirectly, but profoundly.

How thinking works at this level

Fourth-order thinking is reflective and generative.

You pay attention to:

The assumptions embedded in rules and processes

The behaviors rewarded by current structures

The patterns that repeat across projects

Rather than fixing outcomes, you redesign the conditions that produce them.

An analogy

This level is like city planning rather than construction.

You are deciding where roadsgo, how neighborhoods connect, and what rules shape development for decades.

Why this level matters

Fourth-order work creates durability. It allows organizations to adapt without reinventing themselves each time conditions change.

Its impact is often invisible, but long-lasting.

Projects as Transitions, Not Endpoints

As project managers move through these orders, one idea becomes unavoidable.

Projects are not endpoints. They are mechanisms for transition.

Each order expands the time horizon:

First order focuses on delivery

Second order focuses on interaction and adaptation

Third order focuses on strategic evolution

Fourth order focuses on systemic transformation

Success at higher levels cannot be measured by completion alone. It is measured by whether the work moves the organization toward a more capable future state.

As project managers grow, they expand:

The timeframes they consider

The systems they account for

The consequences they anticipate

The definition of success they apply

At its highest expression, project management becomes a form of stewardship. It shapes how organizations learn, decide, and change over time.

Hope this helps.

Nicole