|

I was recently talking with a CPO who asked their roughly 200-team (~2000-person) organization to put together a short biweekly report, made up of a direct update from every team, that they could scan.

There had been a surprising amount of pushback. Not because the report was difficult to produce, since most teams were already doing the underlying update work for internal team reasons, but because, for many people, it signaled micromanagement.

“It sends the message that we don’t trust the teams.”

“It undermines empowerment.”

“We should only do this if leadership plans to act on the information.”

“It goes around managers and directors who need to add context.”

I could sympathize with the team’s concerns. If the intent was to avoid real conversations, then the pushback was warranted. If the report were used to nitpick details or hound middle managers, that would also be a problem. But none of that was actually being proposed. Honestly, the CPO’s request felt reasonable to me, at least as described.

“For me, this is a form of me showing respect for our teams,” the CPO said. “I can only have so many direct conversations, and I don’t want to walk into those based on second-hand information or outdated context. This keeps me up to speed so that when I do talk with teams, the conversation is actually useful. It’s not a replacement for that at all. And it is not a replacement for me talking with my direct reports and skip levels.”

What was really being resisted (I think) was the idea that a senior leader might stay continuously exposed to the messy reality of the organization without first having it filtered, summarized, and made safe. That was the big fear, and something I hear over and over. Teams are used to this kind of information being misused, and to having to gloss over reality when broadcasting updates upward.

This got me thinking about Drucker and mission command. At what point did staying close to frontline reality stop being a leadership responsibility and become seen as micromanagement? What would be so wrong with a CPO maintaining a direct line of sight into the work?

MBO and Mission Command

When Peter Drucker originally described management by objectives (MBO), the overlap with mission command was real:

Focus on outcomes, not tasks

Clear intent instead of micromanagement

Decentralized execution

Trust that people closest to the work decide how

Judgment over compliance. Objectives guide thinking, not replace it

Drucker’s original conception of MBO was closer to mission command than many later interpretations suggest. He described objectives as “direction,” emphasized decentralization as a way to extend leadership responsibility (rather than to shirk it), and grounded management in judgement.

In its best form, MBO said:

“Here’s what matters. You figure out how.”

“Leaders set intent, not instructions.”

“Judgment lives closest to the work.”

That’s very mission-command-adjacent.

But in practice, and in direct opposition to Drucker’s teaching, MBO diverged from mission command. The language of objectives stuck around, while other ideas drifted.

In mission command, intent is meant to be directional, and success is contextual. Judgement remains at the forefront. In MBO, targets often become contracts. Missing the number is considered a failure, regardless of the context. Chasing performative contracts and stale commitments devalues real judgment.

In mission command, leaders are expected to remain continuously exposed to unfolding reality. Feedback is frequent and direct, and is used to tune intent in real time. Escalation in mission command is routine, expected, and safe. It’s not reserved for emergencies. In MBO, leaders often engage with results at review time or when something “big” has gone wrong and an escalation occurs. Teams are implicitly encouraged to handle complexity locally and escalate only when they can no longer cope.

In mission command, accountability is grounded in trust and judgment. In MBO, it often turns into a reporting exercise. Teams learn to manage optics and explanations instead of sharing reality early and often.

Drucker himself later warned that MBO “works—if you know the objectives,” noting that most organizations mistake false certainty for clarity (HBR, 1955).

In Tech…

In tech, we throw around words like “empowerment” and “agency,” but they’re framed primarily in terms of individual autonomy within a theoretically meritocratic system, not in terms of shared doctrine, operating mechanisms, or collectivediscipline. The implicit promise is that if you hire smart people and apply just enough management to let the nerds do their work, good outcomes will naturally follow. It’s a decidedly anti-process, anti-mechanism stance. It assumes judgment is hired for or “earned” through experience, rather than trained, reinforced, and protected over time.

What’s striking is that many tech companies are a bit all over the place.

They espouse empowerment, ownership, and accountability, but don’t have time for practice, or “work around the work.” They ask for loyalty, yet people are often in and out before they really need to own the results of their work. They talk about “relentlessly experimenting on behalf of our customers,” but fail to turn that spirit inwards. They frown on anything that smacks of politics, bureaucracy, or process, but simultaneously rely on rigid filtering and implicit rules about escalation that make it unsafe to surface problems early.

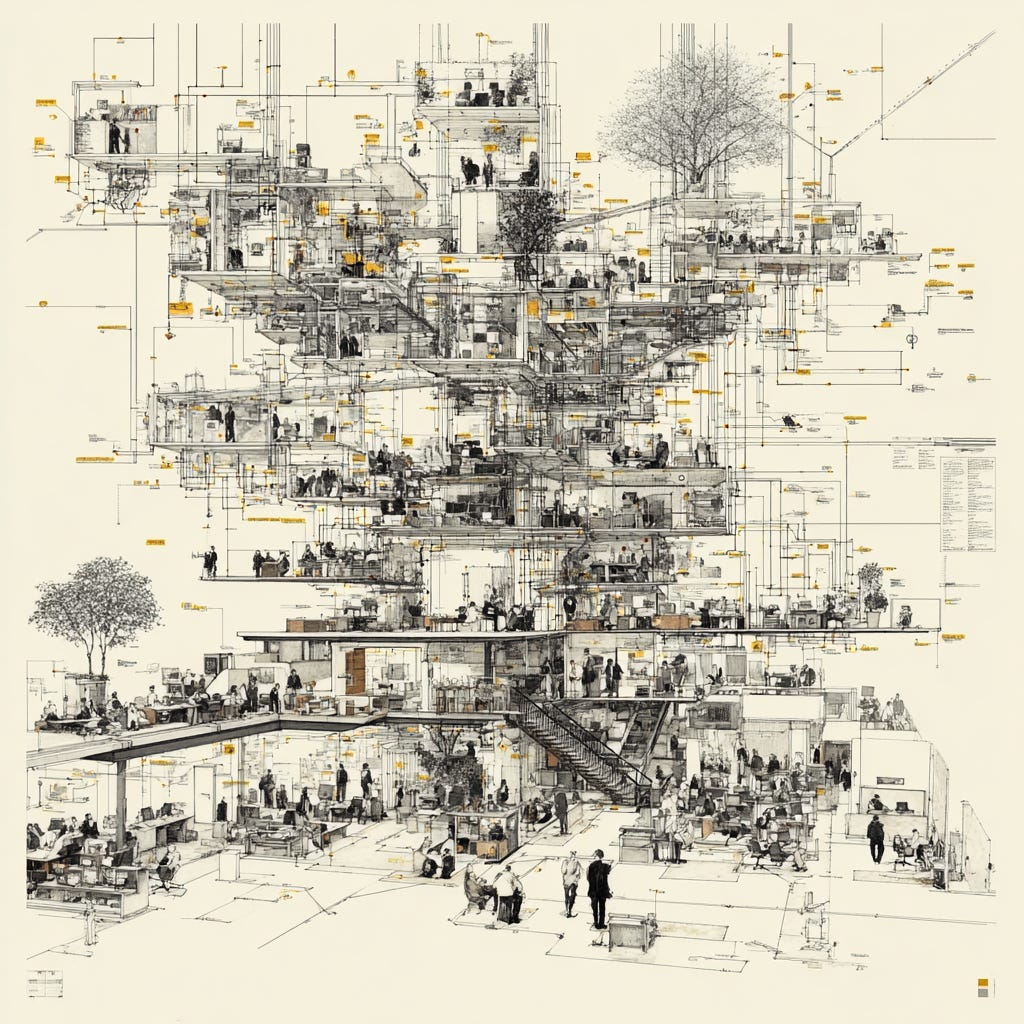

You’ll often find companies with five to seven layers of management, but none of the cultural reinforcement those layers assume. The structure is there; the doctrine isn’t. You can’t expect judgment-based leadership to emerge in environments optimized for churn.

Warranted?

Considering all of this, maybe the team’s pushback was warranted. They were correctly sensing that, in most tech organizations, the conditions for this kind of exposure simply aren’t in place. Without shared doctrine, safe escalation, etc., direct visibility feels like a threat.

But that’s the more interesting question, isn’t it?

What if those conditions could be put in place?

What if staying close to messy reality wasn’t something leaders had to apologize for, and teams didn’t have to defend themselves against, but a shared responsibility supported by real mechanisms, rituals, and trust?

You're currently a free subscriber to The Beautiful Mess. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription.