Sumeet Singh has spent his career placing bets on the future—first as a partner at Andreessen Horowitz, and now as founder and managing partner of Worldbuild. After eight years of investing and conversations with hundreds of AI founders, he’s noticed a troubling pattern: Most are building specialist AI tools the same way they would have built SaaS products a decade ago. In our latest Thesis, he makes the case that this approach is a trap. Drawing on Richard Sutton‘s “bitter lesson”—the idea that scale and compute always beat specialization—Sumeet maps out the two paths he sees for founders who want to build something durable: Either build what models need to get better, or invent entirely new workflows that only AI makes possible. Read on for his breakdown of both paths, and the question every founder and investor should be asking right now.—Kate Lee

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up to get it in your inbox.

I’ve spent the last eight years as an investor—at Andreessen Horowitz and now at my own firm, Worldbuild—watching the same pattern repeat. Software was locked in an era of homogeneity, one dictated by a well-trodden path of fundraising instead of true innovation. It was the same unit economics, same growth curves, and same path to Series C and beyond. Founders optimized for fundraising milestones instead of for building sustainable businesses, leading to companies that raised too much capital at too high valuations.

That era has ended with the advent of generative AI and the end of easy monetary policy. As an investor, I’m excited; AI has finally opened up the potential for real innovation that’s been missing since the mobile revolution. But I see founders building specialist AI products for marketing or finance as if they were building the same subscription software tools of the last decade. Those who are playing by the old framework are about to make a big mistake.

To achieve an outcome attractive enough for venture capital investors in this era (i.e., multi-billion dollar exits), founders today need to absorb Turing Award winner and reinforcement learning pioneer Richard Sutton’s bitter lesson. Sutton’s prognostication was first proven in computer vision—an early AI field in which computers were trained to interpret information from visual images—in the early 2010s when less sophisticated but higher data volume dramatically overthrew the manual programming that had dominated the field for years. Specialization eventually loses out to simpler systems with more compute and more training data. But why is this a bitter lesson? Because it requires that we admit that our intuition that specialized human knowledge is better than scale is wrong—a hard pill to swallow.

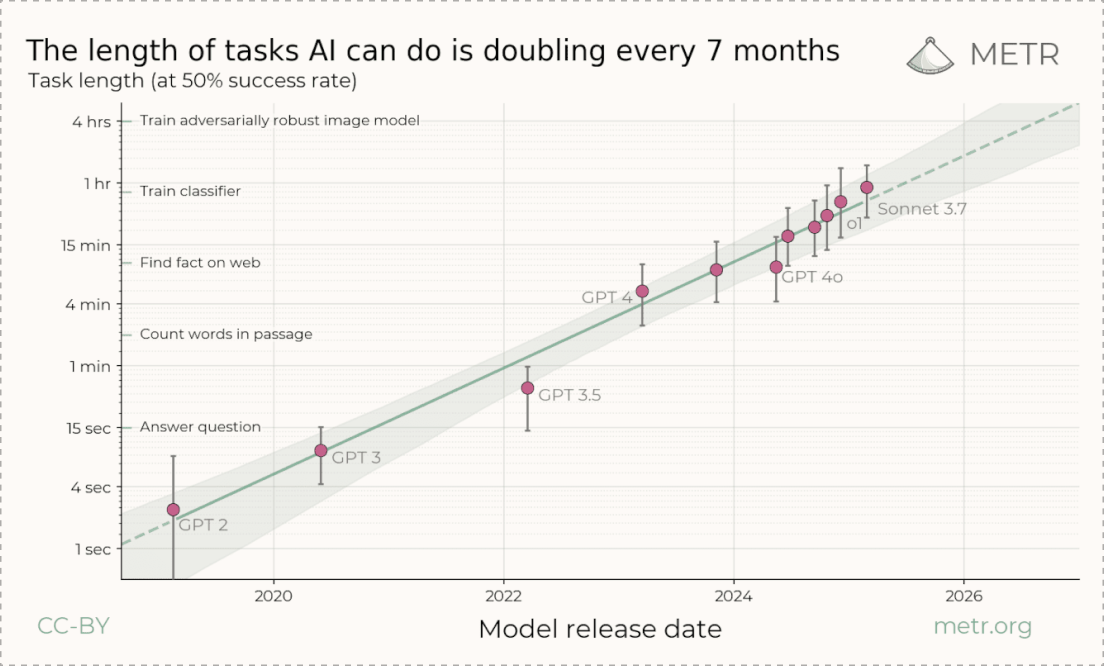

It’s already happening. It’s easy to say in hindsight that it was obvious base models would make early AI writing tools irrelevant, but this fate is coming for every specialist AI tool that bolts on AI models to some existing workflow—whether that’s in finance, legal, and even automatic code generation. Every one of these special tools believes it can create specific workflows with models to beat the base models, but the primary problem is the base models are becoming increasingly capable. The length of tasks that generalist models can achieve is doubling every seven months, as the graph below shows. Their trajectory threatens to swallow any wrapper that is built above them.

After talking to hundreds of early-stage founders building with AI, I see two paths emerging. One leads to the bitter lesson—and irrelevance in 18 months. The other leads to the defining businesses of this era. Those defining business fall into two categories: companies that build what models need to get better—compute, training data, and infrastructure—or companies that discover work that’s only possible because of AI.

Let’s dive into what each category looks like—and how to know which one you’re in.

You don’t lack ideas. You lack time.

Need more time for strategy and creativity? Optimizely Opal’s AI agent platform can free your marketing team from manual work. Automate content creation, campaign execution, personalization, and compliance. Then link your agents together into workflows that take hours off your plate. Use pre-built agents or create your own—each one learns your brand and works seamlessly with your tools.

Stop doing work that AI can do for you and get back to the work that counts.

The first path: The model economy

One way to build alongside the bitter lesson is to think about AI as both a technology to build with and one to build for. With the latter, I am referring to businesses that develop data or infrastructure that enables and enhances model capabilities, as opposed to creating applications that utilize AI as they exist today. I call this the “model economy.”

Many companies building at scale are already riding this shift by selling to labs directly. Those include Oracle, which is increasing its pipeline of contracts to supply compute to model builders to nearly half a trillion dollars. AI cloud companies CoreWeave and Crusoe have similarly been beneficiaries of this wave, pivoting from bitcoin mining to compute and data centers for AI labs, as has Scale AI, with its recent $14 billion investment from Meta to provide high-quality, annotated data for training large language models.

Four big opportunities in the model economy

There are four areas where large, sustainable model economy businesses will be built:

Compute as commodity

AI capabilities will continue scaling along an exponential curve, requiring ever more compute (chips) and energy. But in the short term, expect volatility: Hyperscalers yo-yo between a surplus of GPUs—the specialized processors that power AI—and scarcity within quarters. Microsoft, for example, went from GPU glut to shortage earlier this year. The most durable startups will prepare for both realities: the certainty that AI needs more compute, and the chaos of supply crunches and gluts. We’ve been investing in the “exchange model”—companies that match supply and demand of compute or energy, increase asset utilization (e.g., ensuring chips run at full capacity instead of half), and build mechanisms to trade these resources)—such as AI compute marketplace the San Francisco Compute Company and Fractal Power. These companies withstand volatility and even benefit from it. Meta’s venture into wholesale power trading, a move that would help the company secure flexible power for rapidly growing AI data centers, signals where this is headed. First we’ll trade the electricity that powers AI, then we’ll trade the computing power itself.

AI that lives on your devices

Some AI can’t happen in the cloud due to latency (or real-time response needs), privacy, connectivity, or cost constraints. Take, for example, a hedge fund analyst who wants a model to reason on a trading strategy for days without exposing it to anyone. In this category, specialized hardware and networks run and manage powerful AI models locally, not in someone else’s cloud. Winners will couple hardware and software tightly for AI experiences that happen on a device. Meta, with its continued investment in wearables, is one example, as is upstart Truffle, which is building a computer and operating system for AI models. This category could also include companies that create local AI networks that pool computing capacity from a variety of sources, including computers, graphics cards, gaming consoles, and even robotic fleets.

Data exchanges

To get more sophisticated in their outputs, AI models need increasingly specialized data (e.g., anonymized medical imaging data to produce better answers for health queries). Most of that data today sits inside various businesses, from small companies to large enterprises. New data exchange-like companies could be created to help these businesses understand which data in their possession might be useful for model providers and facilitate licensing deals, such as Reddit licensing data to Google. Alternatively, model providers could dictate what data they need—up-to-date medical research data, for example—and these exchange-like companies could source it.

Security

Today’s security is about defense: firewalls, encryption, and keeping hackers out. Security in the model economy is about offense. These companies will build teams to deliberately break AI systems and uncover the ways they can be manipulated into generating harmful content or corporate espionage. They can then offer these services to large companies so they can patch vulnerabilities before they are exploited.

The second path: Post-skeuomorphic apps

Despite what I have said, not all AI applications—products built on top of foundation models—are doomed.

The ones that will fall prey to the bitter lesson are those that start with an existing workflow, such as updating inventory data, and AI-ify it. The ones that will survive will leverage models’ unique, nuanced properties to invent new workflows that were not technically possible before. I call these “post-skeuomorphic apps.”

Skeuomorphism is the trap of assuming that because you have new technology, it should look like what came before. Early mobile apps fell into this pattern constantly. They replicated the physical world: trash can icons that looked like actual garbage bins, the beer-drinking app that was popular with the first iPhone. But they weren’t exploring what our phones could uniquely do.

The apps that won broke this trap entirely. Uber didn’t digitize the taxi dispatcher’s desk. It asked: What becomes possible when everyone has a phone in their pocket that knows where they are? The phone became a remote control for your life, as investor Matt Cohler has said—for food (DoorDash), for rides (Uber), for groceries (Instacart). They didn’t adapt existing workflows. They invented new ones.

AI is at the exact same inflection point right now. Most AI applications are taking existing processes, such as writing or customer service, and wrapping them in models. The end outcome will likely be the same as what happened to better writing assistants that have seen their advantages eroded by GPT and other foundation models.

The founders who will win are asking a different question: What becomes possible now? What work can we invent that only AI makes possible? Models have unique properties—they can coordinate with other models, learn from every interaction, and generate novel solutions to problems that don’t have predetermined answers. The winning applications will discover workflows that leverage these properties. We probably don’t even know what these workflows look like yet.

Figma offers a useful parallel outside of AI. The founding team’s first step was not just to attempt redesigning the Adobe design suite in a browser. Instead, they experimented with whatWebGL, a technology created in 2011 to enable browsers to tap into your computer’s graphics chip, made possible. The initial experiments with WebGL by Figma co-founder Evan Wallace proved that complex, interactive graphics could run smoothly directly in a browser, which paved the way for Figma’s rendering engine in the browser—a true post-skeuomorphic application.

Three opportunities in post-skeumorphic apps

Post-skeumorphic apps will produce billion-dollar outcomes in three areas:

Coordinating multiple agents at once

I’ve already experienced the potential of post-skeumorphic apps in the realm of multi-agent coordination. As an investor, I use multiple models to act as different personas, prompting each other alongside me, creating a virtual investment committee of sorts. I ask one model to generate a prompt, then feed that prompt into a different model. When I only use a single provider, I notice it gets stuck or loops back on itself. But when I involve multiple models, the results often break out of the sycophantic spiral. (Try this yourself via Andrej Karpathy’s LLM Council.)

Tools that use many agents simultaneously will resist the bitter lesson because the value isn’t in any individual model’s capability, but in the behaviors that arise from their interaction, which reduce hallucinations and enable better evaluations. Rather than being sycophantic, models often rank other models’ outputs higher than their own, creating a more “honest” evaluation system that is less prone to self-confirmation.

Post-skeuomorphic applications will avoid building on a single model and likely won’t just be “co-pilots” that help users in their workflows in a linear way. Instead, they will orchestrate a collective of agents, each with distinct roles and expertise, that learn from every interaction, route work to the right agent at the right time, and get better with every use. They will behave less like software and more like an evolving hive mind.

Simulations at scale

In science especially, AI enables simulations at scale—thousands of computer-run experiments running in parallel. Previously, researchers manually wrote specific, inflexible rules—for, say, how a drug molecule might interact with a protein—ran a few simulations, and hoped they were close to reality.

With GPUs and AI, the workflow is different: Thousands of runs happen in parallel, results feed back into the model, and parameters update continuously. Instead of running one test at a time and waiting for results, the system runs hundreds or thousands simultaneously and learns from all of them at once.

That opens new kinds of work—virtual cells that respond at the system level, protein structures mapped in minutes, and platforms that sort millions of molecular candidates for new drugs without supercomputers or specialized software. The app doesn’t imitate the lab; it defines its own loop of plan, test, learn, repeat—at speed.

Continuous feedback loops

Traditional software relies on discrete inputs and outputs. Model-native applications learn from every interaction and operate in continuous feedback loops that enable them to personalize, optimize, and anticipate user needs.

Monitoring platforms like Datadog watch large software systems to ensure they run properly. Typically, when a problem is spotted, the system alerts a human engineer who then works to fix it. A skeuomorphic AI approach would add smarter dashboards and better root cause suggestions while keeping humans in the decision loop. A truly post-skeuomorphic system eliminates humans entirely through continuous autonomous feedback loops. When API response times spike, the system doesn’t just alert an engineer. Instead, it generates hypotheses about potential causes, spins up parallel infrastructure to safely test fixes, and automatically implements solutions that show improvement. Each intervention teaches the system better prediction and prevention strategies, creating software that observes, diagnoses, and heals itself without human intervention.

The end state looks like self-healing software rather than platforms that simply monitor and alert.

The one question to ask

History rarely gives investors an engraved invitation, but Sutton’s bitter lesson might be the closest thing we get. If scaling laws hold and help models close the gap on domain expertise and specialized features, what looks like a durable edge today may just be temporary arbitrage.

The one question to ask as a venture investor is: Is this company in line to be absorbed by the bitter lesson, or can it thrive by building for scale or true novelty? For founders, the question is even simpler: Are you building something models will replace, or something they need to exist?”

Sumeet Singh is the founder and managing partner of Worldbuild. He was previously a partner at Andreessen Horowitz. You can follow him on X at @sumeet724 and on Linkedin.

To read more essays like this, subscribe to Every, and follow us on X at @every and on LinkedIn.

We build AI tools for readers like you. Write brilliantly with Spiral. Organize files automatically with Sparkle. Deliver yourself from email with Cora. Dictate effortlessly with Monologue.

We also do AI training, adoption, and innovation for companies. Work with us to bring AI into your organization.

Get paid for sharing Every with your friends. Join our referral program.

For sponsorship opportunities, reach out to sponsorships@every.to.